Methods

Media

Gendered language in Japanese appears most often in speech, not writing, so we wanted to work with a conversastional corpus. There are several data sets, like the Corpora for Spontanous Japanese (CSJ), available, however the issue with these is that they are made in a few years, not over a span of a few decades like we needed for our purposes.

We also needed to be able to sufficiently mark-up our texts in XML for further manipulation, so rather than a drama, TV show, or movie, we ultimately decided on song lyrics. Song lyrics are representative of the linguistic features utilized by a culture at a particular point since they employ features that are most popular at the time, and they are also manageable in size.

Choosing popular music from the year 1980 to 2017, we took a sample of 10 songs from each decade (10 from 1980, 10 from 1990, etc). We selected them from the top single ranking charts for each year, mostly by using the lyric website Uta-Net's handy Time Machine feature. Where there were discrepancies between the gender of the singer and the gender of the songwriter (when not the same person), we discounted those songs and picked the next highest ranked single. Thus, in total there are 50 songs, which you can explore by navigating to the Songs page.

Linguistic Features

The linguistic features we chose to focus on were sentence-final particles (SFP’s) and pronouns. There were a handful of other features we noted in our markup, such as the addition of an honorific marker (お- o-, ご- go-) to a noun (marks femininity), but these were few in total.

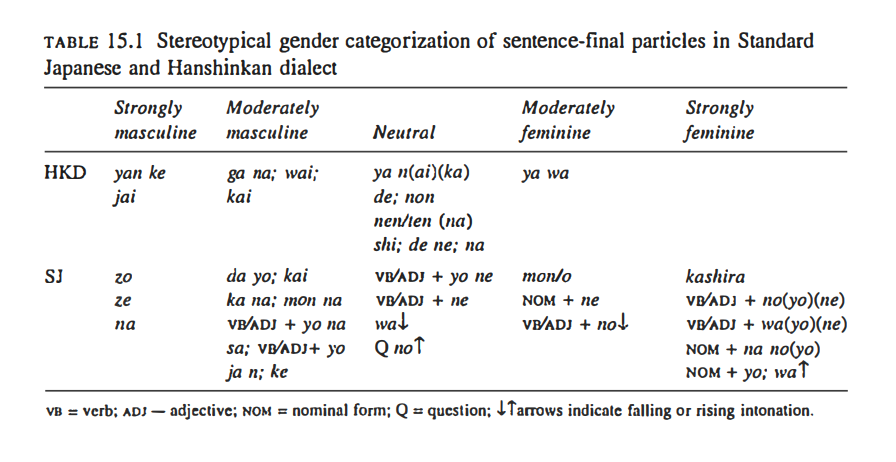

SFP’s are perhaps the easiest gendered language to identify in Japanese, and are added at the end of utterances, often optionally or stylistically. Table 15.1 identifies some of these particles, and how they can differ between dialects.

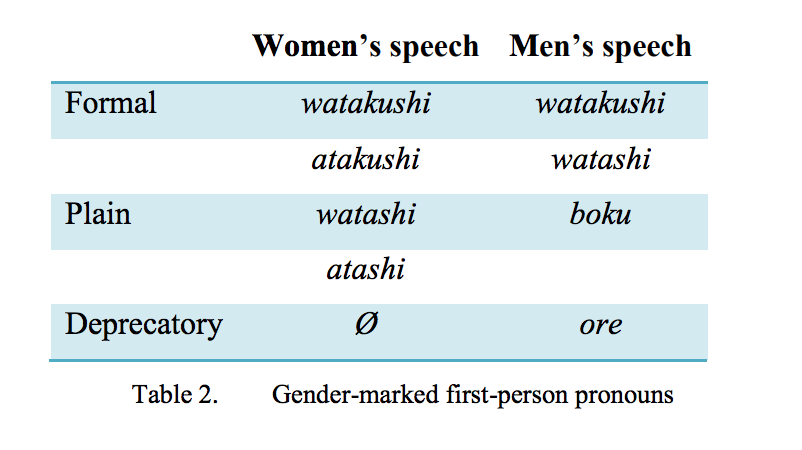

Pronouns in Japanese change depending on the gender of the speaker, the gender of the recipient, and the level of politeness necessary for the situation. For a plain level of politeness, a man could use "君" kimi for the second person, while a women is expected to use "あなた" anata. Table 2 details usage for different first-person pronouns.

Computational Methods

We transcribed the songs first in .txt files, then converted them to XML with both structural and linguistic mark-up. In the structural markup, we accounted for verses and lines. For linguistic mark-up, we tagged features with attributes for the type (SFP or pronoun) and associated gender. After markup was complete, we transformed the XML files to HTML utilizing XSLT. Our visualizations on the Analysis page are made with SVG.

Because SFP’s can vary in their degree of gender markedness as shown in the diagram above, we utilized the same grading scale in our markup of the gender attribute, on a scale from Strongly Feminine > Moderately Feminine > Neutral/Moderately Masculine > Strongly Masculine.

The reason neutral is combined with Moderately Masculine is due to the fact that when Japanese was standardized at the beginning of the twentieth century, it was heavily biased towards male speech, which became “neutral” while women’s speech remained marked as uniquely feminine (Nakamura, 2014). As a result, there are less instances of masculine marked speech than feminine marked speech.